Read every series in the right order

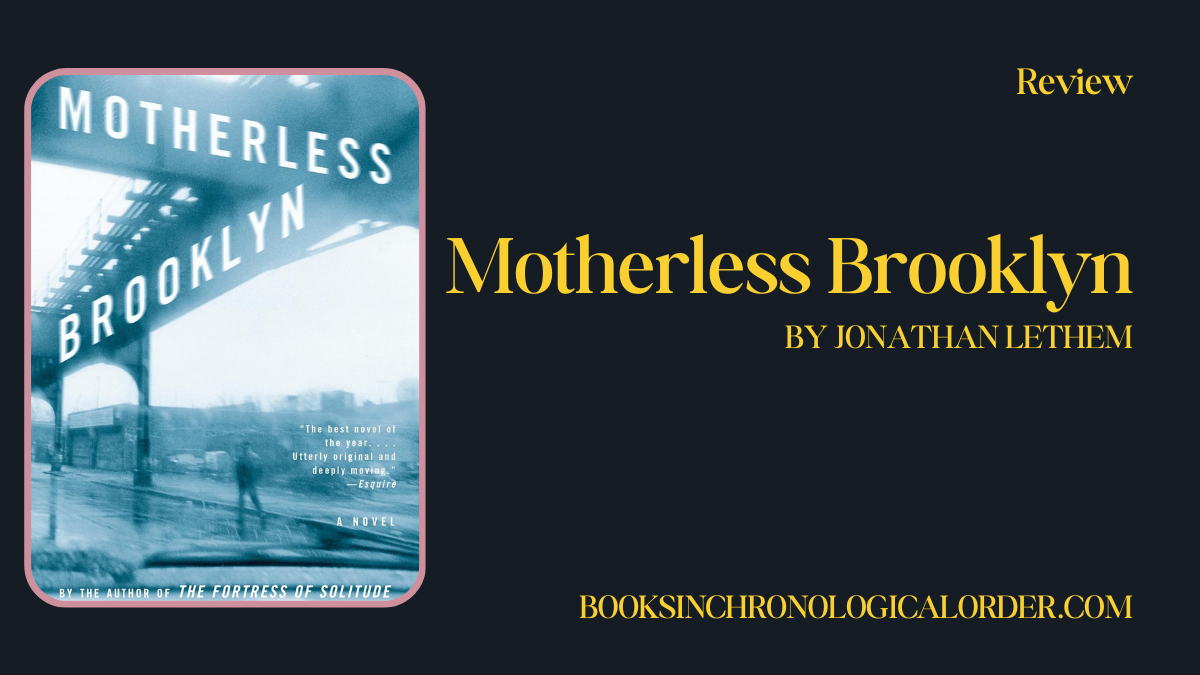

Motherless Brooklyn by Jonathan Lethem — A Personal, Noirish Love Letter to Language, Loyalty, and a City That Can’t Sit Still

Every once in a while a novel hijacks your inner monologue. For a few days after finishing Motherless Brooklyn, I caught myself punning on street signs, tapping out syllables on the steering wheel at red lights, and hearing the click-skip-click of a mind trying to make sense of noise. That’s Lethem’s magic trick. He gives you Lionel Essrog—an orphan turned small-time gumshoe in a sham car service/detective front—whose Tourette’s makes him both unreliable and laser-true. The tics are intrusive, yes, but they’re also interpretive; they’re the soundtrack to a brain that refuses to smooth out jagged edges.

Plot-wise, the scaffolding is familiar and comforting: a mentor (Frank Minna) is murdered; the surrogate family (the self-styled “Minna Men”) fractures; our narrator decides to get answers even if it means getting pummeled. But the book’s real engine isn’t “whodunit?” so much as “how does a mind like Lionel’s move through the world and make meaning?” He’s profane and tender, embarrassingly earnest one second and Chandler-slick the next. You don’t read this purely for the twist. You read it to live for a while inside a consciousness that shouldn’t be funny but often is, shouldn’t be poetic but somehow sings.

If you’re wary of “Big Idea” novels where a condition becomes a gimmick, I was right there with you before page one. And then Lethem won me. Lionel’s Tourette’s is never a moralizing lecture nor a party trick. It’s embodied, metabolized—part obstacle, part secret weapon. When people underestimate him, he hears what they miss. When language breaks, it breaks open, and something true slips out.

Brooklyn, for its part, is not a backdrop. It is an accomplice—an urban Tourette’s of honks and haggles, stoops and steam, White Castle grease and Zen center quietude. Like the best New York novels, Motherless Brooklyn knows that the city rewrites you sentence by sentence.

And that’s what this is: a literary noir that loves its genre enough to tease it, a character study that refuses pity, a mystery that knows solutions matter less than the people we become getting there.

Table of Contents

Why Motherless Brooklyn

1) The voice is a feat—and a feast.

Lethem invites you into Lionel’s mind with such confidence that the tics become not just noise but a prosody. Wordplay is compulsion and craft. Digressions don’t derail; they reveal. As a reader, you stop “tolerating” the voice and start trusting it. That’s rare.

2) It’s genre-savvy without being smug.

This is a detective story that knows its lineage—Marlowe’s shadows, Hammett’s angles, Pynchon’s giddy conspiracies—and still strides out on its own. The parody moments land (Mob guys, inscrutable corporate heavies, a case that tries to zig when you expect a zag), but they serve character first. Lethem’s winks are affectionate, not superior.

3) Lionel’s disability is integrated, not instrumentalized.

Tourette’s isn’t a cute eccentricity. It affects every action scene, every conversation, every silence. And yet the novel rejects the patronizing arc of “broken man becomes whole.” Lionel is already whole—flawed and whole—learning how to wield what he’s got.

4) Found family matters.

Frank Minna is a grifter and a guardian, a man who plucked four boys from an orphanage and taught them how to bluff, drive, tail, and keep a secret. The grief when he’s gone isn’t genre-grief; it’s filial. Seeing the Minna Men jostle for hierarchy after his death feels like watching siblings reorganize a house after the parent leaves. It hurts because it’s specific.

5) The city is alive.

Lethem’s Brooklyn is granular: diners glazed with fluorescent fatigue, church basements, offices that smell like toner and old lies, cabs that are not cabs. If you’ve lived in a place long enough to name the deli guy’s brother, you’ll recognize the texture—the sense that geography is fate and coincidence is just a neighborhood’s way of flexing.

6) It’s funny. Like, genuinely.

The humor is sometimes slapstick (imagine suppressing a bark in front of a man with a gun) and sometimes linguistic (palindromic riffs on a name until it collapses into taffy). But it’s never at Lionel’s expense. The laughs relieve pressure, then deepen it.

7) It’s re-readable.

Because the pleasure isn’t only in solution but in sensibility, this is the rare crime novel that benefits from knowing what’s coming. You re-hear the line that telegraphed a betrayal. You catch the throwaway image that was a clue and a metaphor.

Themes That Stuck With Me

1) Language as Symptom, Language as Sword

Lionel’s mouth runs—sometimes aloud, sometimes under-breath. But the point isn’t to dazzle us with verbal fireworks; it’s to show how words can be both cage and key. Tourette’s makes him blurt, echo, repeat, pun, grind syllables until they turn to dust. That behavior is involuntary, often humiliating, always exhausting. And yet those same tendencies sharpen his perception. He hears the grain in a voice, notices the burr on a consonant when someone lies, picks up the nervous rhythm in a pause. Lethem’s trick is to keep both realities present: the pain of being betrayed by your tongue and the gift of listening like a poet.

The novel also insists that language is social. People complete (or complicate) each other’s sentences. Frank Minna’s patter—compressions, coinages, insults disguised as endearments—becomes a dialect the Minna Men speak among themselves. When the maestro goes missing, their speech frays. They lose fluency in their small tribe. It’s a gorgeous way to depict grief: as an idiom going extinct.

2) Consciousness, Split and Stitched

Sometimes Lionel talks about his Tourette’s like it’s a second self, an imp that pushes him from behind. Other times it’s simply him, embodied and relentless. The effect is almost phenomenological—an inquiry into what a “self” consists of when agency is contested. Is Lionel the man who counts, barks, and taps? Or the man suppressing and steering? Lethem’s answer is “yes.” The condition becomes a lens through which to view all the novel’s dualities: cop/criminal, sacred/profane, city/monastery, sincerity/shtick. Everyone here is split—performing roles, negotiating impulses. Lionel is just the most honest about his split.

3) Loyalty and the Cost of Belonging

Frank rescues the boys from anonymity, gives them jobs, suits, nicknames, and—most potent—attention. In that adoption is a covenant. When Frank dies, the question isn’t just who pulled the trigger, but who broke faith. The Minna Men’s bickering over turf and memory is painful because it feels like arguments siblings have after a will is read. Lethem nails the way loyalty curdles into defensiveness, the way grief makes auditors of us all. And he asks a harder question: When a father figure is both savior and scammer, how do you honor the gift without worshipping the flaw?

4) Brooklyn as Character (and as Tourette’s)

One of the novel’s best metaphors is offhand: New York as a Tourettic city—itchy, staccato, self-interrupting, full of rules and rule-breaking. You can map the case by subway line, by bridge, by the zigzags of a stakeout. But the real cartography is social—Zen centers, diner booths, union halls, back offices where favors accrue interest. When people talk about “Brooklyn novels,” they often mean posture. This isn’t that. It’s an ethics: notice everything, hustle kindly when you can, pull a favor from your pocket before you pull a gun.

5) Satire, Sincerity, and the Long Shadow of Noir

Lethem knows the nods you’re expecting: the cigarette in the ashtray, the girl who might save or ruin you, the heavy you can’t outpunch but might outtalk. He gives you those pleasures, then lets them be human. The femme fatale isn’t all fatal; the heavy is ridiculous when the moment requires it; the wisecrack reveals need as often as superiority. The joke, in other words, isn’t on the genre but on the way we cling to genre to avoid feeling. Lionel resists that dodge: he feels, then riffs, then feels again.

6) Disability Without Sermonizing

Representation can go sidewise so quickly—into pity porn, into inspiration sloganeering, into research-dump. Lethem skates the thinnest ice and doesn’t crack it. He shows you a man who’s hyper-competent one scene and humiliated the next; a man whose symptoms terrify him in front of armed men and seduce him into verbal fireworks when he should stay quiet. He lets you laugh (with Lionel, never at him) and lets you squirm. That’s respect.

7) Orphans, Adoption, and Alternative Families

The “Minna Men” set-up could have been just a quirky origin story. Instead, it becomes the book’s moral infrastructure. These are boys who were nobody, given names and hats and a clubhouse. The masquerade (car service pretending to be PI firm pretending to be something clean) parallels the masquerade of family; it’s fake and it’s real. When that scaffolding collapses, Lionel isn’t just solving a case. He’s trying to salvage a self.

8) Spirituality in Strange Places

The book opens with a Zen stakeout: quiet room, ticking body. It’s a clash that could signal irony—holy hush meets gumshoe grit—but Lethem plays it straight. There’s a sincere curiosity about systems that reframe desire and silence. Even the mobbed-up offices sometimes read like chapels where men pray to money and legacy, lighting candles of plausible deniability. This isn’t a “religious” novel, but it is a spiritual one insofar as it respects the rituals people create to organize chaos.

9) Comedy as Armor and Aperture

“Funny” in this book isn’t a flavor; it’s a tactic. Jokes deflect danger; riffs relieve shame; deadpan buys time. But comedy also opens the story up, letting oxygen in so the darker scenes don’t suffocate. It’s an old noir truth: if you can’t get a laugh in the room, you probably can’t get the truth either.

10) Mystery as a Means, Not an End

If your thrillers live or die by the twist, prepare to recalibrate. Lethem gives you enough switchbacks to feel honored as a genre reader, but the deepest satisfactions are character ones: a phone call placed too late, a fight survived through humiliation rather than heroics, a room that still smells like the man who’s gone. It’s the rare crime novel where a perfectly tied-off plot might have ruined it.

My Final Thoughts

I finished Motherless Brooklyn with that rare combination of satisfaction and hunger. Satisfaction because the book closes its own loop—you understand the murder, the betrayals, the power games. Hunger because Lionel’s voice keeps echoing; you want to keep hearing the world in his syntax a little longer.

I also felt grateful. Grateful that Lethem insists on complexity without shouting about it. Grateful that he makes a disabled narrator neither mascot nor martyr. Grateful, too, for the way he loves his influences. He doesn’t posture against Chandler and Hammett; he trades bars with them, gives them a grin, and then keeps the solo moving.

Is the plot perfectly plausible? No. Does it need to be? Also no. This isn’t a police procedural asking you to admire chain-of-custody rigor. It’s a literary-noir hybrid after something messier: a plausible soul. On that score, it’s one of the best books I’ve read in years that made me both think and care, sentence by sentence.

If you’re a reader who needs tidy, you may bristle when the novel pauses for Lionel’s inner fireworks. If you’re a reader who fears “literary” means humorless, fear not. If you’re a reader who hopes a crime novel can be a character novel first, welcome home.

I’ll keep this one on the shelf—partly because I want to lend it, partly because I want to re-read it, and mostly because I like the idea that its voice can shout from there when my own language gets lazy.

Read This If You…

- …crave a detective story that’s less about the gun and more about what the gun does to the person holding it.

- …love New York novels that treat neighborhoods like ecosystems and diners like churches.

- …enjoy narrators whose rhythms are a plot of their own.

- …are curious (or cautious) about disability narratives done with respect and bite.

- …collect literary crime that tips its hat to Chandler and then writes in its own ink.

- …want a book club selection that sparks conversation about voice, representation, humor, and genre.

Comparison Chart With Similar Reads

| Title & Author | Why It Pairs Well with Motherless Brooklyn | Overlapping Themes | Vibe / Reading Feel | Start Here If… |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Fortress of Solitude — Jonathan Lethem | Another Lethem New York symphony; boyhood, friendship, race, music, and myth in 1970s–80s Brooklyn. | Brooklyn as character; identity; friendship | Expansive, nostalgic, formally playful | You want Lethem’s voice at epic scale. |

| Inherent Vice — Thomas Pynchon | Stoner noir parodies the PI form while loving it; language hijinks galore. | Satiric noir; SoCal counterculture; linguistic play | Loopy, free-associative, sun-baked | You want maximum genre-mischief with a grin. |

| The Yiddish Policemen’s Union — Michael Chabon | Alt-history detective novel with lush prose and a wounded, witty shamus. | Wordplay; Jewish identity; noir homage | Lush, clever, world-building heavy | You want big style with big heart. |

| Claire DeWitt and the City of the Dead — Sara Gran | Visionary PI novel where clues feel like dreams and truth has a cost. | Mysticism; detective-as-seeker; grief | Haunting, fragmentary, cult-classic | You like your noir metaphysical. |

| The Long Goodbye — Raymond Chandler | The existential gold standard—moral fatigue, friendship, and betrayal under neon. | Noir DNA; loyalty; voice-driven narration | Elegant, weary, quotable | You want the classic that taught the rest to talk. |

| The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time — Mark Haddon | Neurodivergent narrator makes investigation a lens on mind and family. | Consciousness; difference; family | Precise, tender, deceptively simple | You want a different condition-driven perspective. |

| The Last Policeman — Ben H. Winters | Detective story on the eve of apocalypse; what’s the point of truth when the world’s ending? | Purpose; stoicism; procedural-with-twist | Clean, melancholy, propulsive | You want a big premise with quiet humanity. |

| Manhattan Noir (Akashic Series) — ed. by Lawrence Block | Short, sharp slices of NYC crime across boroughs; a chorus of voices. | Urban grit; moral ambiguity | Varied, punchy, streetwise | You want bite-sized shadows between novels. |